When I returned to "the world" in January, 1969 and saw how the media portrayed American armed forces’ actions in Vietnam, and when I heard many law students and "legal experts" cry that the war was illegal, I wrote this paper one year after I was at Khe Sanh.

You may find some of the arguments about U.S. involvement in Vietnam enlightening as you hear more and more about Kosovo. Consider the issues about the President using troops in an undeclared war, the nature of the internal conflict--civil war or genocide, and the lack of congressional and public support. Sound familiar?

THE LEGALITY OF THE VIETNAM WAR

for

Professor G. K. Reiblich

Current Constitutional Problems

April 1969

The United States is presently engaged in an armed conflict in Vietnam which has already exceeded the death toll of the Korean conflict and is draining manpower and money which many people believe could be put to better use here at home. It is difficult for part of the American public to see why this nation is sending troops to fight a de facto war in a foreign country when it appears that the war, being on the other side of the world, is not in the interest of our national self-defense. What is even more frustrating to many Americans is that there seems to be no immediate end to the war in sight. As a result of the aforementioned observations, popular dissent has become evident and has manifested itself in many forms--peace marches, war protests, draft card burnings, refusals to induction into the military, newspaper editorials, congressional dissenting, and even litigation against the Government of the United States by individuals who do not wish to participate in what has been termed an "illegal war".

The purpose of this paper is to explore the Vietnam conflict in this context--its legality. The legality of the Vietnam conflict has two distinct aspects: the justifiability of the United States intervention under international law with which I will deal in the first part of this paper, and the constitutionality of such action under domestic law which is treated later on.

Although United States commitment of troops in actual combat in Vietnam is relatively new, the present conflict in Vietnam has its origins in over fifty years of French colonial rule in Indochina. French control over the Indo-Chinese peninsula began with military conquest beginning in the 1850's and gradually extended over half a century to include all of what is now Laos,

Cambodia, and Vietnam. In 1899, the French organized the area as the French Indo-Chinese Union consisting of the French Protectorates of Laos and Cambodia, and the French colony of Cochin-China in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam, and the French Protectorates of Annam in central Vietnam, and Tonkin in northern Vietnam. The Japanese supplanted French rule in the 1940s, and their rule lasted until the capitulation of the Japanese forces in 1945.

The Potsdam Conference of 1945 gave the Indochina territories taken from the Japanese to Great Britain for the areas south of the sixteenth parallel and to the Republic of China for the areas north of that parallel. Meanwhile the Vietminh (League for the Independence of Vietnam), led by Ho Chi Minh, proclaimed the independence of the democratic Republic of Vietnam and established a government for all of Vietnam with its seat at Hanoi.

The British who controlled southern Vietnam rearmed the French and relinquished authority over the area to them while the Chinese retained military control over the north and permitted the Vietminh to function as a de facto civil regime. On March 6, 1946, the French Government recognized the Republic of Vietnam as a free state but not as an independent state and agreed with the Vietminh Government to enter into friendly negotiations on the future status of Indochina. Negotiations between the Vietminh and the French were unsuccessful; and by December 1946, the French Indo-chinese War had begun which ended in military defeat for the French Union Forces at Dienbienphu and in political capitulation at the Geneva Conference of 1954.

Prior to the Geneva Conference, the French Government agreed on June 5, 1948 to recognize an independent "State of Vietnam" within the French Union with former Emperor Bao Dai as its head. This "State of Vietnam" was recognized by the United States on February 7, 1950 as an independent state within the French Union. The Soviet Union recognized the Vietminh regime in North Vietnam as The Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the same year. Each regime, Bao Dai's in the south, and Ho Chi Minh's in the north, claimed authority over the whole of Vietnam.1

With the defeat of The French Union Forces at Dienbienphu came the Geneva Conference. The Geneva Accords of 1954 established the date and hour for a cease-fire in Vietnam, drew a "provisional military demarcation line" with a demilitarized zone on both sides, and required an exchange of prisoners and the phased regroupment of Vietminh Forces from the south to the north and The French Union Forces from the north to the south. The introduction into Vietnam of troop reinforcements and new military equipment (except for replacement and repair) was prohibited. The armed forces of each party were required to respect the demilitarized zone and The territory of the other zone.

Applicable sections of The agreement are as follows:

Agreement Between the Commander in Chief of the French Union Forces in Indo-China and the Commander in Chief of the People's Army of Vietnam on the Cessation of Hostilities in Vietnam Signed at Geneva, July 20, 1954

Chapter I

Provisional Military Demarcation Line and Demilitarized Zone

Article 1

A provisional military demarcation line shall be fixed on either side of which the forces of the two parties shall be regrouped after their withdrawal, the forces of the People's Army of Vietnam to the north of the line and the forces of the French Union to the south.

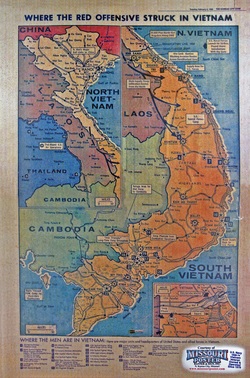

The provisional military demarcation line is fixed as shown on the map attached (see Map No. 1).

It is also agreed that a demilitarized zone shall be established on either side of the demarcation line, to a width of not more than 5 kms. from it, to act as a buffer zone and avoid any incidents which might result in the resumption of hostilities.2

Article 1 clearly designates the military demarcation line which is to be honored by both parties to the agreement. Incidents which might "result in the resumption of hostilities" are to be avoided.

Chapter II, article 10 reads:

The Commanders of the Forces on each side, on the one side the Commander in Chief of the French Union Forces in Indo-China and on the other side the Commander in Chief of the

People's Army of Vietnam, shall order and enforce the complete cessation of all hostilities in Vietnam by all armed forces under their control, including all units and personnel of the ground, naval, and air force.3

The Geneva Accords spell out that there will be a cessation of hostilities and the commanders of the two zones respectively will enforce the terms of the agreement and respect the demilitarized zone and the territory of the other zone. The adherence of either zone to any military alliance and the use of either zone for the resumption of hostilities or to "further an aggressive policy" were prohibited.

The International Control Commission was established composed of India, Canada, and Poland with India as Chairman. The task of the Commission was to supervise the proper execution of the provisions of the Cease-Fire Agreement. General elections that would result in the reunification of Vietnam were required to be held in July 1956 under the supervision of the Internal Control Commission.4

During the five years following the Geneva Conference of 1954, The Hanoi regime developed a covert political-military organization in South Vietnam based on Communist cadres it had ordered to stay in the south, contrary to provisions of the Geneva Accords. Thus, we see an immediate and substantial violation of the Geneva Accords. The activities of this covert organization were directed toward the kidnaping and assassination of civilian officials--acts of terrorism that were perpetrated in increasing numbers. In the three year period from 1959 to 1961, the North Vietnam Regime infiltrated an estimated 10,000 men into the south.

This was clearly in violation of the Geneva Accords. It is estimated that 13,000 additional personnel were infiltrated in 1962 and by the end of 1964, North Vietnam may well have moved over 4,000 armed and unarmed guerrillas into South Vietnam.5

South Vietnam was now under armed attack from the north. The term "armed attack" has significance in the SEATO Treaty (to be discussed) in determining whether intervention by The United States was justified under certain provision of the treaty; however, to avoid dwelling on semantics, let us assume that thousands of armed and unarmed personnel infiltrated from North Vietnam to the south could be considered an "armed attack" in the broadest sense of the term. Acts of kidnaping, assassination of civilian officials, and other acts of terrorism should also be included in the concept of "armed attack" since guerrilla warfare is characterized by these acts rather than a blatant "troops on line" type of show of force characteristic of an invasion or attack in conventional warfare.

The Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, here after called the SEATO alliance, was signed at Manila on September 3,

1954. The parties to the treaty were Australia, France, New

Zealand, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It was entered into force as to The United States on February 19, 1955. Apparently, the parties to the treaty realized that the treaty area--the general area of Southeast Asia--was still in a state of turmoil; and in order to protect the interest of those countries who were trying to govern themselves and remain free from Communist aggression and exploitation, and in order to promote a general state of peace in the treaty area, the parties to the SEATO alliance expressed their goals in the treaty:

The parties to this Treaty, Recognizing the sovereign equality of all the parties, Reiterating their faith in the purposes and principles set forth in the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments, Reaffirming that, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, they uphold the principle of equal rights and self- determination of peoples, and Declaring that they will earnestly strive by every peaceful means to promote self- government and to secure it and are able to undertake its responsibilities, Desiring to strengthen the fabric of peace and freedom and to uphold the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law, and to promote the economic well- being and development of all peoples in the treaty area, Intending to declare publicly and formally their sense of unity, so that any potential aggressor will appreciate that the parties stand together in the area, and

Desiring further to coordinate their efforts for collective defense for the preservation of peace and security,

Therefore agree as follows:

The parties to the treaty have stated their desire to "strengthen the fabric of peace and freedom and to uphold the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law, and to promote the economic well-being and development of all peoples in the treaty area"; and they wish to declare publicly their "sense of unity so that any potential aggressor will appreciate that the parties stand together in the area...". They are trying to ensure peace in an area which had just experienced the Indo-Chinese War.

Article I goes on to state:

The parties undertake, as set forth in the Chapter of the United Nations, to settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful mean in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered, and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.6

Article IV, paragraph 1 reads:

Each party recognizes that aggression by means of armed attack in the treaty area against any of the parties or against any state or territory which the parties by unanimous agreement may hereafter designate, would endanger its own peace and safety, and agrees that it will in that event act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes. Measures taken under this paragraph shall be immediately reported to the Security Council of the United Nations.7

This provision, supra, is where the term "armed attack" becomes critical because if South Vietnam was in fact subjected to an armed attack as indicated by the findings of the International Control Commission, then the United States is merely fulfilling its obligation as expressed in the SEATO alliance to "act to meet the common danger". On the other hand, if South Vietnam was not subjected to an "armed attack", then paragraph 2 of Article IV would be controlling.

Article IV, paragraph 2 reads:

If in the opinion of any of the parties, the inviolability or the integrity of the territory or the sovereignty or political independence of any party in the treaty area or of any other state or territory to which the provisions of paragraph 1 of this article from time to time apply is threatened in any way other than by armed attack or is affected or threatened by any fact or situation which might endanger the peace of the area, the Parties shall consult immediately in order to agree on the measure which should be taken for the common defense.8

Apparently, South Vietnam and the United States were under the impression that South Vietnam was subjected to an armed attack by North Vietnam cadres. As I have noted earlier, an armed attack does not have to have the formality and magnitude of large forces invading other large forces or civilian areas. Small units, characteristic of guerrilla warfare, can conduct an armed attack and even create a state of war.

Corpus Juris Secundum defines war:

War, in the broad sense, is a properly conducted contest of armed public forces, or in a narrower sense, a state of affairs during the continuance of which the parties to the war may legally exercise force against each other..... It is not necessary, to constitute war, that both parties shall be acknowledged as independent nations or sovereign states, but war may exist where one of the belligerents claims sovereign rights as against the other.9

It seems clear that the acts of aggression (infiltration of armed troops to the south) and terrorism by North Vietnam can be termed as an "armed attack" and could be legally acted upon by the United States as a party to the SEATO alliance. The authorization for such action would be paragraph 1 of Article IV of the treaty.

South Vietnam, not a member of the SEATO alliance, but within the treaty area (area of Southeast Asia) could act in its own interest of self-defense to ward off the attack from the north. The United Nations Charter recognizes the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against any member of the United Nations. Article-51 of the Charter of the United Nations reads:

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of The United Nations, until The Security Council has taken the measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.10

According to Article 51, the United Nations encourages self-defense of its members against an armed attack; and although South Vietnam was not a member of the United Nations; it would be absurd and inconsistent with international goals of world peace and security to assume that South Vietnam would not have the right to take individual or collective self-defense against an armed attack. The United Nations Charter nowhere contains any provision designed to deprive non-members of the right of self-defense against an armed attack. The State Department Memorandum concerning the legality of United States participation in The Vietnam war has stated:

The Republic of Vietnam in the South has been recognized as a separate international entity by approximately sixty governments the world over. It has been admitted as a member of a number of the specialized agencies of the United Nations.. The United Nations General Assembly in 1957 voted to recommend South Vietnam for membership in the Organization, and its admission was frustrated only by the veto of the Soviet Union in the Security Council. In any event there is no warrant for the suggestion that one zone of a temporarily divided state-- whether it be Germany, Korea, or Vietnam-- can be legally overrun by armed forces from the other zone, crossing the internationally recognized line of demarcation between the two. Any such doctrine would subvert the international agreement establishing the line of demarcation and would pose grave dangers to international peace.11

Thus, it is consistent with principles of international law concerning maintaining world peace and security that South Vietnam defend itself against aggression from North Vietnam. Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations encourages self-defense against armed attacks, and the SEATO alliance encourages action by any of its members to maintain peace and security in the treaty area (thus the United States involvement).

Opponents to the legality of the Vietnam war have contended that South Vietnam violated an important provision of the Geneva accords by refusing to hold general elections in July of 1956; therefore, the cause of South Vietnam has no greater legality to it than does the cause of North Vietnam which violated the Geneva Accords by infiltrating armed personnel to the south. This contention can only be held invalid when the circumstances are analyzed.

The Geneva Accords contemplated the reunification of the two parts of Vietnam by containing a provision for general elections to be held in July, 1956 in order to obtain a "free expression of the national will." The Accords stated that "consultations will be held on this subject between the competent representative authorities of the two zones from July 20, 1955 onwards." South Vietnam did not sign the cease-fire agreement of 1954 and did not adhere to the Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference. The South Vietnamese Government at that time gave notice of its objections in particular to the election provisions of the Accords.

Whether or nor the provisions were binding on South Vietnam is questionable, but even assuming they were, the South Vietnamese Government's failure to engage in consultations in 1955 with a view to holding elections in 1956 involved no breach of obligation. The conditions in North Vietnam were not conducive to making possible any free and meaningful expression of popular will.

General Giap, Defense Minister of North Vietnam, in addressing the Tenth Congress of the North Vietnamese Communist Party in October 1956, publicly acknowledged that the Communist leaders were running a police state where executions, terror, and torture were commonplace. A nationwide election would not have represented what the people wanted as no one in the north would have dared to vote except as directed; and since a substantial majority of the Vietnamese people living north of the seventeenth parallel would have voted Communist, the country would have been relinquished to the Communists without regard to the will of the people. The purpose of the elections was to get a "free expression of the national will", and this purpose would not have been met had the elections been held.12 The acts of terrorism conducted by personnel from the north on persons in the south also would have negated a free expression of the will of the people in the south had they voted.

At this point, let us focus our attention on the President of the United States and his power to commit troops to the aid of a foreign country. The SEATO alliance was a treaty advised and consented to by the Senate of The United States. The President as Commander in Chief of The armed forces and as chief executor of the laws of the land is authorized to commit troops to Vietnam in accordance with the provisions of the SEATO alliance and principles of international law (i.e., maintaining peace and security in a treaty area).

The actions of the Congress, particularly the Joint Resolution of August 10, 1964, also authorize the President to commit troops to Vietnam. Whereas two United States naval destroyers were attacked by Communist forces in The Gulf of Tonkin, both the Senate and the House of Representatives resolved to approve and support whatever actions the President, as Commander in Chief, deemed necessary to take to repel armed attacks against United States forces and to maintain peace and security in Southeast Asia. The Southeast Asia Resolution states:

Whereas naval units of The Communists regime of Vietnam in violation of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law, have deliberately and repeatedly attacked United States naval vessels lawfully present in international waters, and have thereby created a serious threat to international peace.....

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of The United States of America in Congress assembled,

That the Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further

aggression.

Section 2

The United States regards as vital to its national interest and to world peace the maintenance of international peace and security in Southeast Asia.

Consonant with the Constitution of the United States and the Charter of The United Nations and in accordance with its obligations under the Southeast Asia Collective Defense

Treaty, the United States is, therefore, prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force,to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in defense of its freedom.

Section 3

The resolution shall expire when the President shall determine that the peace and security of the area is reasonably assured by international conditions created by action of the United Nations or otherwise, except that it may be terminated earlier by concurrent resolution of Congress.13

By the Congressional Resolution, Congress has merely reaffirmed what the Constitution of the United States has said: the President is Commander in Chief of the armed forces and chief executor of the laws of the land (treaties included of course).

The SEATO alliance (one of The laws of the land) is being acted upon when the President sends troops to the "treaty area" to help restore peace and security. Thus, in this way, the President is acting in the capacity--chief executor of one of the laws of the land and Commander in Chief of the armed forces. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (another law of the land) spells out the people's will that the President "take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force" in order to maintain international peace and security in Southeast Asia.

The Constitution of the United States gives certain powers to the President. Article II, section 1 says, "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America." Article II, section 2 says, "The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States." Article II, section 3 says, "... he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed."14

While there has been dispute over the extent to which inherent or implied powers of his office allow the President to use force without prior statutory authorization in other areas--notably to aid civil authorities or to protect states from domestic violence--the authority of the President to use the armed forces, at least in the absence of restrictive legislation, in order to enforce within the United States substantial federal interests evidenced by the nation's laws is now generally accepted.15

In In Re Debs, where certain railroad officials were obstructing railroad traffic and the flow of mails, the Supreme Court said, "The entire strength of the nation may be used to enforce in any part of the land the full and free exercise of all national powers and the security of all rights entrusted by the Constitution to its care. The strong arm of the national

government may be put forth to brush away all obstructions to the freedom of interstate commerce or the transportation of the mails. If the emergency arises, the army of the Nation, and all its militia, are at the service of the Nation to compel obedience to its laws."16

The President as Commander in Chief can use troops not only to enforce the national’s laws and protect substantial federal interests, but he can use troops to defend the nation against a sudden attack without a declaration of war from Congress.

Though the war-declaring clause was intended to give Congress the power to initiate war in most cases, there is the view that at least in the case of a sudden attack the President was able to respond without prior congressional sanction, even though such response would amount to making war. The rationale for conceding the existence of this power in the President no doubt lies in the recognition that where the defense of the country itself is at stake, there is simply no room for procedural restrictions which might hamper the republic’s ability to survive intact. Thus viewed, the power need not rest on any specific provision of the Constitution; as a necessary concomitant of sovereignly itself, the inherent right of national self-defense gives the President full power to defend the country against sudden attack with whatever means are at his disposal as Commander in Chief.17

The Prize Cases approved of the expanding power of the President to make war without prior authorization under the theory of defense during the Civil War. The Supreme Court said, "If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the President is not only authorized but bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war, but is bound to accept the challenge without waiting for any special legislative authority. And whether the hostile party be a foreign invader, or States organized in rebellion, it is none the less a war, although the declaration of it be unilateral."18

The court upheld the validity of Lincoln's proclamation of a blockade of the Southern ports. The President was recognized as possessing unlimited power to wage war in defending against a war begun through invasion or rebellion, and he was to be the sole judge of when such invasion or rebellion amounted to "war," thereby authorizing assumption of his full defensive powers.

What is the relation between the President's use of troops in the interest of national self-defense as exemplified in the Prize Cases and the President's use of troops engaged in a de facto war in Vietnam as authorized under provisions of the SEATO alliance and The Gulf bf Tonkin Resolution? The trend today is to consider "self-defense" of a nation to extend beyond the nation's immediate boundaries. The State Department Memorandum, supra, suggests that a direct attack is no longer a realistic prerequisite for exercise of the President's power to act unilaterally in national self-defense. Because of the delicate balance of power among nations as well as the frightening technology of modern warfare, an attack on a foreign country may just as surely threaten our security as a direct attack on United States territory.

The twentieth century and the experience of two world wars have created the idea of linking American defense with extraterritorial security interests. National security became world security and there emerged the thesis of collective self-defense. The United Nations Charter explicitly recognizes inherent right of individual or collective self-defense, and the United States proceeded accordingly in the years following World War II to conclude a number of regional and bilateral security agreements. By the agreements, the United States generally agreed to regard an attack on a member nation as threatening its own safety and to assist in defensive measures. The SEATO alliance is one such agreement.19

There are recent examples of overseas conflicts where a president has exercised his constitutionally given authority to use the nation’s troops--the invasion of South Korea during President Truman’s administration, the Arab threat to Lebanon during Eisenhower’s, the sending of missiles to Cuba during Kennedy’s, and the disorder in the Dominican Republic during Johnson’s administration. These examples are not true cases of where the President sent troops abroad in the interest of national self-defense, but they are better designated as the exercise of the President's power to protect American interests abroad. On the other hand, where the President has sent troops to Vietnam, it is a somewhat different story.. Even if to some people the SEATO alliance provision to maintain peace and security in Southeast Asia (an area on the other side of the world in relation to the United States) does not appear to be in the interest of self-defense of the United States, certainly it is convincing that the sending of troops to Southeast Asia (after American warships had been deliberately and maliciously attacked in international waters) is in the interest of self-defense. Thus, the self-defense argument, perhaps not as strong as the argument that we are engaging in a war to help South Vietnam rid itself of aggression, is still tenable. Apparently the Congress and President of the United States think so as implied by the Southeast Asia Resolution.

Critics of the President's sending troops to Vietnam say he has usurped congressional authority to declare war. Article 1, section 8 of the Constitution says that Congress shall have the power to declare war. The President has not infringed on that power; Congress may declare wars when the situations arise, but in cases of conflicts of a lesser magnitude than a large scale war, the President has traditionally taken action without a formal declaration of war.

In an article, The War in Vietnam: Unconstitutional, Justiciable, and, Jurisdictionally, Attackable, the war in Vietnam is bitterly criticized; none-the-less, the article points out that the President has, on some one hundred twenty-five occasions, without congressional declaration of war, ordered the armed forces to take some action or to maintain some position abroad. It also points out that "the one use of force upon which the current war might be supported is the Korean war, which was a long sustained and large-scale foreign military operation fought without a congressional declaration of war."20

Another argument in favor of the President sending troops abroad without congressional declaration of war is that the President is the nation’s leader in international relations. In United States V. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., the Supreme Court held that a Joint Resolution of Congress authorizing the President to determine whether or not the sale of United States arms and munitions of war to foreign countries engaged in war inhibited peace in the warring countries was a constitutional delegation of legislative power to the Executive.

"It is quite apparent that if in the maintenance of our international relations, embarrassment--perhaps serious embarrassment--is to be avoided and success for our aims achieved, congressional legislation which is to be made effective through negotiations and inquiry within the international field must often accord to the President a degree of discretion and freedom from statutory restriction which would not be admissible were domestic affairs alone involved. Moreover, he, not Congress, has the better opportunity of knowing the conditions which prevail in foreign countries; and especially is this true in time of war."21

The President as the nation's leader in foreign relations must on occasion act to protect American interests abroad; and as the SEATO alliance acknowledged America's interest in peace and security in Southeast Asia, the President by sending troops to South Vietnam is protectinq these interests.

Another critic of the Vietnam war, Stanley Faulkner, in an article, The War in Vietnam: Is It Constitutional?, comments that the President does not constitutionally have the right to commit troops to Vietnam.

"The powers of the President, both in war and in peace are not absolute. The framers of our Constitution did not enumerate the powers of the President until after the powers of Congress were detailed in article I. The issue as to where to place the power of declaring war was carefully deliberated by the framers. "22

As has been noted earlier, the President has traditionally taken measures in situations somewhat less than a large scale war without a declaration of war from Congress. Faulkner's reasoning has no bearing on the Vietnam war because there is no declaration of war by Congress. The President is acting not under a declaration of war, but rather he is acting in the capacity as leader in international affairs and is protecting our national interest abroad as other presidents have done in the past.

Faulkner believes that the Supreme Court should scrutinize the acts of the President with respect to Vietnam to determine their legality. He believes that the court should not hide any longer behind the "thicket" of the "political question." He cites the Youngstown case as a leading example of judicial scrutiny of executive powers. President Truman issued an order to seize steel plants during a nationwide strike. The Korean conflict was on and he believed the strike would jeopardize national defense. The plaintiffs, leaders in the steel industry, reguested the Supreme Court to enjoin Secretary of Commerce, Sawyer, from enforcing an Executive Order to seize steel plants. The court held that the President does not have undefined powers and that he exceeded his enumerated powers in the present case.23 The decision in the Youngstown case is not applicable to the President's sending troops to Vietnam as the case decided that he could not seize steel mills on strike rather than he could not send troops to engage in combat overseas. There is a difference between seizure of private property and sending troops abroad under provisions of an international treaty and a congressional resolution.

CONCLUSIONS:

In determining the legality of United States involvement in the Vietnam war, either in the context of international law or the constitutionality of the President's sending troops there without a declaration of war from Congress, one must examine the problem in the context of its time. The world situation, the international goal of peace and security, the struggle of small new nations to govern themselves, the concept of war--both large scale international war and small scale guerilla war, the expanding powers of the President in international relations--all of these factors influence why the United States is involved in the Vietnam war; and they influence one’s attitude toward the war’s legality or illegality.

Whatever The arguments may be for the war’s legality or illegality, the Vietnam war and the United States involvement therein is something that cannot be decided in a legal context. The legality of The war is simply a nonjusticiable issue. Who should decide if the war is legal or illegal? The Supreme Court of the United States? If so, the Supreme Court would be passing judgment upon actions of the other two branches of our Federal Government, the Legislative and the Executive, in an area--international relations--which the Supreme Court has already acknowledged the President to be the leader (Curtiss-Wright case, supra).

The Supreme Court has recognized its limitations and has refrained from deciding a political question when another branch of the Federal Government can take action. In particular, the Court has refused to decide recent cases which involve the legality of the war in Vietnam. In Mora vs. McNamara, 389 U.S. 934 (1967), the petitioners were drafted~into the United States Army in late 1965, and six months later were ordered to a West Coast replacement station for shipment to Vietnam. They brought this suit to prevent the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of the Army from carrying out these orders, and requested a declaratory judgment that the present United States military activity in Vietnam is "illegal". The Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari.24

Until some "arch tribunal" declares the United States involvement in the Vietnam conflict to be illegal, under present international law principles and our constitutional law principles, the legality of the war in Vietnam can only be affirmed.

Footnotes:

1. Daniel Partan, Legal Aspects of the Vietnam Conflict, 46 Boston, University Law Review 281, 283 (1966).

2. Geneva Accords Richard A. Falk, Editor, The Vietnam War and International Law, Princeton University Press; Princeton, New Jersey (1968) at p. 543.

3. Id., p. 545.

4. Memorandum of Law, Dept. of State, The Legality of United States Participation in the Defense of Vietnam, 75 Yale Law Journal 1084 (1966) at p. 1097.

5. Id., p. 1085.

6. Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, Sept. 8, 1954, (1955) 1 ACED 81, TAS. No. 3170 at p. 82.

7. Id., p. 83.

8. Id., p. 83.

9. 93 CGS, War and National Defense, 1 at p. 6 (1946).

10. Memorandum of Law, Dept. of State, supra note 4, at p.1097.

11. Id., p. 1090.

12. Id., p. 1099.

13. Southeast Asia Resolution, Pub. L. No. 88-408, (H.J. Res. 1145), 78 Stat. 384 (1964).

14. Constitution of the United States, Library of Congress, Lester S. Jayson, Supervising Editor, U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington: 1964.

15. Note, Congress, The President, And the Power to Commit Forces to Combat, 81 Harvard Law Review l77l (l968) at p. 1775.

16. In Re Debs, 158 U.S. 564, 582 (1895).

17. Note, Congress, The President, And the Power to Commit Forces to Combat, supra note 15, at p. 1778.

18. Prize Cases, 67 U.S. (2 Black) 635, 668 (1863).

19 Note, Congress, The President, And the Power to Commit Forces to Combat, supra note 15, at p. 1782.

20. The War in Vietnam: Unconstitutional, Just~able, and Jurisdictionally Attackable, 16 Kansas Law Review 449 (1968) at p. 470.

21. United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.,

299 U.S. 304, 320 (1936).

22. Stanley Faulkner, The War in Vietnam: Is It Constitutional? 56 Georgetown Law Journal 1132 (1968) at p. 1132.

23. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

24. Mora V. McNamara, 389 U.S. 934 (1967).

CITATION OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

In Re Debs, 158 U.S. 564 (1895).

Mora V. McNamara, 389 U.S. 934 (1967).

Prize Cases--Frigate Amy Warwick; Schooner Creashak; Barque Hathaway; Schooner Brilliantine, 67 U.S. (2 Black) 635 (1863).

United States V. Curtis-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304 (1936).

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. V. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

DOCUMENTS

Constitution of the United States of America, Library of Congress, Lester S. Jason, Supervising Editor, U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington: 1964.

Geneva Accords signed July 20, 1954

Richard A. Falk, Editor, The Vietnam War and International Law, Princeton University Press; Princeton, New Jersey (1968).

Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, Sept. 8, 1954, (1955) 1 ACED 81, TAS. No. 3170.

Southeast Asia Resolution, Pub. L. No. 88-408, (H.J. Res. 1145), 78 Stat. 384 (1964).

MISCELLANEOUS

93 CGS, War and National Defense 1 at p. 6 (1946).

Stanley Faulkner, The War in Vietnam: Is It

Constitutional?, 56 Georgetown Law Journal 1132 (1968).

Memorandum of Law, Dept. of State, The Legality of United States Participation in the Defense of Vietnam, 75 Yale Law Journal 1084 (1966).

Daniel Partan, Legal Aspects of the Vietnam Conflict, 46 Boston University Law Review 281 (1966).

Note, Congress, The President, And The Power to Commit Forces to Combat, 81 Harvard Law Review 1771 (1968).

The War in-Vietnam: Unconstitutional, Justiciable, and Jurisdictionally Attackable, 16 Kansas Law Review 449 (1968).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed